Aanbieding Cuvee Grande Colline en Idyll Rose

Cuvee Grande Colline van € 9.45 nu voor € 7.95

Muscat/ Vilana / Sauvignon Blanc

en

Idyll Rose van € 9.45 nu voor € 7.95

Kotsifali / Syrah

Cuvee Grande Colline van € 9.45 nu voor € 7.95

Muscat/ Vilana / Sauvignon Blanc

en

Idyll Rose van € 9.45 nu voor € 7.95

Kotsifali / Syrah

Aankomend weekend staat Kretawijnen op het Noordelijk Wijnevent in de Harmonie te Leeuwarden. Mocht je het leuk vinden om hierbij te zijn laat het ons dan weten. Wij hebben nog een aantal vrij kaarten voor beide dagen op = op.

Met vriendelijke wijngroet,

Merel en Ruud

Ter ere van het 50-jarige bestaan van het familie wijnhuis Lyrarakis is er een aantal rode flessen wijn beschikbaar in een king-size maat. Magnum 1,5 liter, Jeroboam 3 liter en Imperial 6 liter. Unieke collector items!

Puur genot voor de komende feestdagen of om te bewaren voor jouw speciale moment. Kretawijnen biedt deze wijnen aan tegen een scherpe prijs.

Inschrijven kan tot uiterlijk maandag 3 oktober 2016 via info@kretawijnen.nl

Na de bestelling krijg je van Kretawijnen per omgaande de factuur met het verzoek tot betaling. Kretawijnen garandeert je dat de flessen ruim voor de Kerstdagen worden geleverd.

Onderstaand de beschikbare flessen. De prijs is incl. BTW en gratis thuisbezorgd. Op=Op Voor de details zie de wijnen op de webshop van www.kretawijnen.nl

50 jaar Lyrarakis 1966-2016

Magnum 1,5 liter (2 flessen)

• Last Supper 2012 rood € 22

• Syrah-Kotsifali 2013 rood € 26

• Mandilari Plakoura 2012 rood € 30

• Cabernet-Merlot 2013 rood € 40

• Cabernet-Merlot 2012 rood € 42

• Symbolo 2012 rood € 58

Jeroboam 3 liter (4 flessen)

• Last Supper 2012 rood € 42

• Syrah-Kotsifali 2013 rood € 56

• Mandilari Plakoura 2012 rood € 59

• Cabernet-Merlot 2013 rood € 84

• Symbolo 2012 rood € 116

Imperial 6 liter (8 flessen)

• Syrah-Kotsifali 2013 rood € 108

• Cabernet-Merlot 2013 rood € 160

Met vriendelijke wijngroet,

Merel & Ruud

Lekker lang buiten zijn en genieten. Kretawijnen heeft een mooie aanbieding voor jou.

Mandilari rosé normaal € 6.50 nu voor € 6,-

Gemaakt van 100 % mandilari een echte Kretenzer druif.

Heerlijk als aperitief in de zon met wat kleine hapjes erbij.

Veel tonen van fruit, zacht en soepel te drinken.

Idyll rosé normaal € 9,45 nu voor € 8,45

70 % syrah en 30 % kotsifali.

Goed om te combineren bij de bbq bij gegrild en gekruid vlees.

Donkere fruit tonen, vol en stevig in de smaak.

Deze aanbieding duurt tot en met zondag 11 september of zolang de voorraad strekt.

Geniet van deze mooie ‘kinderen van de zon’.

Yamas/Proost!

Met vriendelijke wijngroet van

Merel & Ruud

Zondag vierde Kretawijnen met 30 wijnliefhebbers het Grieks Pasen. Het Groene kerkje in Lambertschaag schitterde in het West-Friese landschap met bloeiende bomen en tulpenvelden. De kachel stond aan om de kou te verdrijven maar we werden deze dag verblijd met een stralende zon. Zo ook werden we verblijd met een mooie groep wijnliefhebbers en ons gezelschap werd één grote familie. Iedereen werd begroet met de Kretenzer bubbel de ZaZaZu. We vervolgden met 9 wijnen waarvan 5 wijnen met een spijs voor het mondgevoel. Leuke reacties over de combinatie wijn & spijs. Daarna met z’n allen aan de huisgemaakte Griekse gerechten met een glas wijn naar keuze. We eindigden met de dessertwijn Malvasia of Crete met de petit four Sweeter van, witte chocolade, cranberries en amandelen van CHOVE. Wijn & Chocolade, Kretawijnen & CHOVE een spannend stel!

Al onze gasten, hartelijk dank voor jullie aanwezigheid, gezelligheid en ook voor jullie mooie bestellingen! Kretawijnen krijgt mede door jullie meer naamsbekendheid, efcharisto poli, veel dank! Geniet van de wijnen van deze mooie “kinderen van de zon”, yamas!

Met vriendelijke wijngroet van Merel & Ruud.

The sun shone; the wind howled. Ten degrees of latitude further north, and this would be a ski run. Crete, though, is the chin on Europe’s face; we’re even south of Pantelleria here.

There was indeed snow on the three mountain ranges which give Crete its brooding physical presence. Here, though, at 650 metres, there was just stone, light, mute vines – and a picnic table that threatened to soar in the blast, like the spying griffon vultures overhead.

This was Vassilis and Anna Topsis’s Pirovolikes Vineyard, and there was a bottle of their 2014 Vilana, made by Lyrarakis, on the table, alongside Anna’s home-baked meat, vegetable and cheese pastries. As we pitched up (literally: the track to the vineyard was steep and deeply rutted), she was gathering wild golden thistle (scolymus, in fact a member of the chicory family) to cook later. We ate the pastries and drank the wine. It was fresh and incisive, like the wind: a splash of lemon, shattered stones, bitter herbs.

They were proud of the moment, and the wine; and I was, in a way, awed by them, for I could see that neither wine nor the moment was easily won from nature. They keep goats, for milk, cheese and meat; they bake their own bread, in a wood-fired oven they light every two weeks. They live from the vine and the olive.

Like their forebears – for the last 3,500 years. We’d just visited the Minoan wine-press at Vathipetro, part of a palace complex built around 1580 BCE (probably less than a hundred years after the Santorini explosion). Later that afternoon, in the village of Agios Thomás, my companions and I stood on the edge of a giant, open-air treading tank – chiseled out of a limestone boulder the size of a small house during the centuries when Crete was the productive overseas Republic of Venice known as Candia (1205-1669)

There’s no automatic correlation, of course, between the length of a tradition and its present-day call on our attentions – but in Crete’s case, something very interesting is going on. Here’s why.

It’s big: this is the Mediterranean’s fifth largest island, and the main wine-growing area, set back from Heraklion, is Greece’s second largest wine district. But it’s a late starter in the modern wine race: phylloxera, astonishingly, only reached Crete in the 1970s.

Not only is replanting recent, but the island had the double handicap (or so it now seems) of having been replanted largely with international varieties, since that was what domestic and tourist consumers wanted at the time. Crete, though, has a splendid suite of indigenous varieties – and it’s wine from those which has best export potential. They’ve stepped shyly into the limelight as Greece’s successive economic crises have eroded domestic consumption, leading Cretans to rethink the vineyard mix.

Remember, too, that most Cretan viticulture is high-altitude: up to 858 metres above sea level. That fact, combined with evidently happy adaption of indigenous varieties and some first-class limestones and marls, means that Cretan wine defeats the expectations generated by its latitude.

Most of it (68 per cent) is white, for a start, and it’s the whites which for the time being show the most technical assurance. They’re usually fresh, scented, nuanced, haunting and graceful, notched between 12.5% and 13%. The reds are a stronger, often light in colour, but remarkably structured – and wines of both colours impress for their complex, secondary flavour profiles, something seemingly built into the Greek gene bank: so much more than simple fruit, and very food-friendly.

Ah yes, food. Why aren’t there more Cretan restaurants around the world? With its delicacy and colour, its embrace of vegetables and its retrained use of meat, its use of a unique range of indigenous herbs and foraged greens with simply prepared fish and cheese, and its artful celebration of olive oil and of bread, both fresh and dried, it seems perfectly in tune with the gastronomic zeitgeist: light on the stomach, pretty on the eye, rooted in a culture and a place.

The final Cretan call on our attention is the price of its wines. Before touring the hills above Heraklion, I spent a day tasting. There were many wines which weren’t merely good but were original and exciting – and often on sale in Crete at well under six or seven euros a bottle. The British chain Marks & Spencer is one retailer which has noticed this combination of value and intrigue; it’s due to list a 2014 white from the indigenous Dafni grape variety (also from Lyrarakis) in June, priced at just under £10. Other importers, particularly those searching out intriguing wine for restaurants, should take a look.

Here are eleven fascinating wines based on indigenous Cretan varieties and blends. There are four PDOs (appellations) on Crete – Dafnes (for dry and sweet Liatiko), Archanes (for dry red Kotsifali and Mandilari), Peza (for white Vilana and dry red Kotsifali and Mandilari) and Sitia (for white Vilana and Thrapsathiri blends, and for dry or sweet red Liatiko and Mandilari). For the time being, though, and very sensibly, most Cretan producers simply use the comprehensible and easy-to-pronouce PGI of ‘Crete’ itself.

Alexakis, Vidiano 2015

Vidiano is the fragrant charmer among Cretan whites: I have recommended three, but there are a dozen or more on the island which amply merit export. Interestingly, it has a wide range of styles, perhaps depending on the altitude at which it is grown. This version from regional pioneer Alexakis, from two vineyards at 550m and 600m, is almost Viognier-like, with floral and ginger notes and some pleasing mid-palate richness. 89

Diamantakis, Vidiano 2015

The Vidiano from the skilled family team at Diamantakis is grown in exposed, stony vineyards at 500 m, and resembles a Roussanne from Savoie more than a Viognier: creamy, blossomy scents with an elegant, poised and almost crisp palate, backed by more petal-foam. 90

Klados, Great Hawk, Vidiano 2015

It’s worth mentioning the Klados Vidiano since it is grown in Rethymno, the coastal city between Heraklion and Hania where the variety originated. This is just 12%, but there’s no sense of shortness or rawness; indeed it’s vinous, long and sappy, if a little less fragrant than the wines from the Heraklion hinterland mentioned above. 88

Lyrarakis, Armi Vineyard, Thrapsathiri 2015

The Thrapsathiri variety, at least when grown at 600 m under the sheer rock walls of Mount Ida (also known as Psiloritis), is almost Albarinho-like: delicate perfumes and a cascade of sweet fruits and flowers. Barrel-fermentation plus a couple of months in oak just tease in a little cream. 91

Monastery of Toplou, Thrapsathiri-Vilana 2015

This blend of two indigenous varieties doesn’t come from the high-altitude vineyards above Heraklion, but from a unique, remote, red-clay terroir at the far east of the island, close to Sitia. Suddenly we are in the presence of a much richer, denser, more succulent white wine, packed with wild grass and summer-fruit notes. 91

Silva, Psithiros, Moschato Spinas 2013

Psithiros means ‘whisper’; the variety here is Moschato Spinas: a distinctive Cretan strain of white Muscat which provides remarkably complete dry wines, like this chewy, vinous, pear-fruited wine from the Daskalakis family’s fine range of wines. 89

Idaia, Vidiano 2015

The beautifully labeled Idaia Vidiano is grown at a higher altitude still (600m). Pure, fresh and vivid yet with beguiling inner complexity, this has a soft sappiness and leafiness which works well with its gentle green-apple fruit (just 12,5%). Impressive refreshment and subtlety here. 91

Lyrarakis, Plakoura Vineyard, Mandilari 2013

Mandilari is considered Crete’s greatest red grape, with potentially extravagant tannins and acids, though it can be almost deficient in alcohol unless cropped very low. This 13% version had just three days on the skins (with the IPT reaching 74 on the third day); after old-oak ageing, though, it is a lively, almost refreshing red wine with a smooth central palate; the tannins only grown palpable at the end. Plum flavours with a Byzantine note: incense on the nose, and something almost like mastic on the palate. 91

Douloufakis, Dafnios, Dafnes 2014

The Cretans are almost apologetic about the Liatiko grape variety because of its generally light colours and need for protective handling to keep oxidation at bay, and it is mostly used to make pleasant but unexceptional sweet wines. I fell in love with its dry wines, though, since they have huge personality, a beguiling inner sweetness and ample structuring tannins — of a much plumper style than the tannins of Mandilari. It can resemble traditionally aged Piedmontese reds (owner Nikolas Douloufakis, as it happens, studied in Alba). Sweet, exotic red-fruits scents and a perfumed, grippy, haunting flavour make this wine from the PDO of Dafnes a reference bottle. 92

Milarakis Estate, Peza 2010

Peza is the most widely used of the island’s PDOs, and this now-mature blend of 80% Kotsifali with 20% Mantilari puts it through its paces: balanced, lively and pure, with wild sloe and cranberry fruits. Light and refreshing (12.8%), yet with complexity to finish, too. 89

Monastery of Toplou, Liatiko-Mandilari 2013

Grown on lower-lying, stony schist soils in the arid, windy conditions of Sitia, and skillfully vinified by Manolis Stafilakis, this blend of 80% Liatiko with 20% Mandilari is compelling and unique, deeply satisfying and Italianate in style: sweet apple and sweet mushroom scents, with a nutty, fleshy, tannic, low-acid palate packed with more mushrooms, autumn leaves and almost honeyed red fruits, despite being a dry wine. 92

De laatste tijd richt ik me met proeven op kleinschalig geproduceerde wijnen, uit wat minder bekende streken. Dan hoor ik regelmatig dat een wijn gemaakt is van “een druif die met uitsterven bedreigd was, maar nu weer tot volle bloei is gebracht”. En wel door “een producent die ergens op een verlaten wijngaard nog een paar stokken van deze druif heeft ontdekt”. Dat vraagt wel om enige scepsis.

In deze moderne tijden is wijn maken een weinig romantische bezigheid. Alles wordt klinisch onderzocht. Op rijpheid, op hygiëne, op weerstand of op herkomst. Het DNA kan worden vastgesteld en zo kan worden bekeken of de druif dezelfde is als de wijnmakers beweren. De een noemt zijn lokale druif Zus en de ander Zo, en elk weet niet beter dan dat het verschillende, volledig eigen druiven zijn. DNA laat geen spaan heel van de bewering en het blijken volkomen identieke druiven te zijn, dus weg unieke druif. Of andersom: een producent kan beweren dat Zus dezelfde druif is als Zo, zodat Zus daar status aan kan ontlenen. DNA biedt de oplossing. Er blijkt werkelijk geen enkele relatie te bestaan tussen de twee rassen en helaas is Zus slechts in naam gerelateerd aan Zo, maar niet genetisch.

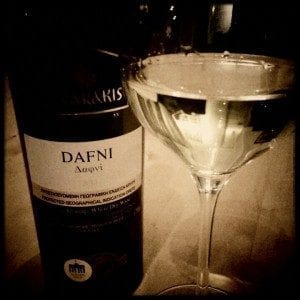

De Dafni is een oude druif uit Kreta en je raadt het al: bijna uitgestorven en opnieuw tot bloei gebracht. Volkomen uniek. Echt waar. Herintroduceerd door de Kretenzische wijnmaker Lyrarakis. En gelukkig maar, want ik had deze ervaring niet willen missen. De Lyrarakis Dafni 2013 heeft een fascinerende geur en smaak, die lastig is te duiden in termen van fruit. Hij geeft je een heel nieuw kader. En wat voor één! Laurier is de naamgever van deze druif; die vinken we af. Verder verse groene kruiden als salie, tijm en rozemarijn, artisjok, groene olijven en jeneverbes (de struik). Ook nog de heerlijke bergkruidenthee van Kreta en een fijne frisheid na.

Wij hebben hem genuttigd met een salade van gegrilde venkel, groene aspergetips, gerookte zalm, bladpeterselie, kwarteleitjes, kalamata olijven en parmesan. Met als resultaat versmelting. Alsof je de wijn kunt eten en de salade kunt drinken.

Wine Weekend 21 en 22 november. Als je binnenkomt op de wijnbeurs van het Wine Weekend krijg je gelijk een gezellig wijngevoel. Geen opgesmukte luxe stands maar marktstalletje met lichtjes erin brengen je gelijk in een stemming van… eens lekker wijn te gaan proeven. En dat er goede wijnen waren te proeven, kon je gelijk bij de eerste stand al ervaren waar importeurs hun best deden hun wijnen aan de man te brengen maar niet opdringerig waren. Echter, sommige schonken zulke kleine beetjes wijn dat je niet echt goed kon proeven. Maar waar zit dat probleem dan? Vroeg ik. “Veel mensen slikken alle wijnen direct door en dan ben je bij nummer 20 aardig teut, zei een lachende importeur. Dit is een beurs direct gericht op de consument en niet voor professionals, die spugen alles uit, dat maakt het anders en meer ongedwongen”. De stemming zat er gelijk goed in.

Vorig jaar waren enkele nog onervaren, zelfs stuntelige, wijnhandelaren op deze proeverij. Maar nu ook enkele top- importeurs die mooie wijnen presenteerden zoals Wijn op Dronk die absoluut het hoogste niveau wijnen liet proeven uit hoofdzakelijk Frankrijk. Meest van kleine wijnhuizen die exclusieve wijnen maken. Er is weinig van. Snel proeven en vooral snel bestellen maar.

Een grote verrassing voor mij was de importeur Kreta Wijnen die een serie wijnen liet proeven van het Griekse wijnhuis Lyrarakis. Enkele jaren volg ik dat huis en ik vond nooit dat ze bijzondere wijnen maakten. Maar nu heeft Lyrarakis een metamorfose ondergaan en brengen ze wijnen op de markt die breed inzetbaar zijn en goed gemaakt. Balans, goede zuren, fris-fruit en krachtige mooie afdronk van de meeste wijnen. Wat is daar gebeurt met de kwaliteit. Goed zo. Merel Heuzer (foto rechts) van Kreta Wijnen zal zeker haar bijdrage hebben geleverd aan deze kwaliteitsslag.